By Stewart, March 2022

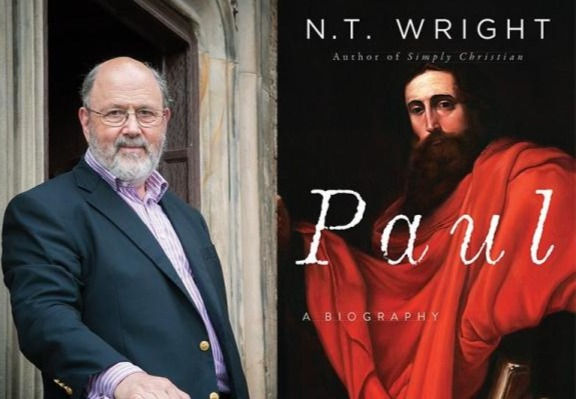

For decades, N.T. Wright has been a staple in Christian literature, producing works such as Simply Christian, Surprised by Hope, Signposts, and many more. He is a prolific writer who has consistently shown himself to be among today’s most thoughtful Christian academics. Those who are familiar with Wright’s work will no doubt be familiar with his sophisticated eschatology that often challenges many modern Christian’s theology, my own notwithstanding. I would be inclined to imagine that if N.T. Wright was here to interject, he would say something along the lines of “I am looking to understand scripture not through the lens of our 21st-century sensibilities, but through the cultural, historical, and religious mindset that the Biblical writers would have had when producing the books of the Bible”. It is this passion that Wright has for pealing away today’s interpretations and understandings of Biblical texts in search for the Word’s authentic meaning that interested me when I came across Paul: A Biography. Wright has consistently proven himself to be an even-handed leader in Christian thought due to his earnest acknowledgement of the various influences we modern audiences unknowingly possess when interpreting scripture while also not falling into that trap of idolizing the early Church and supposing that they understood some secret truth that we have since lost - a reality that he makes very clear through this book. Instead, Paul offers readers an insightful look into the life of the titular figure that, while not always revelatory, proves itself to be a solid read for anyone looking to learn about life and ministry of Paul the Apostle.

The first topic that Wright addresses in his book is the cultural ethos a young Paul would have grown up in, specifically the religious atmosphere which permeated every aspect of Jewish life. However, I must make a small amendment to that previous statement. Wright thoughtfully notes that Paul’s Judaism would not exactly mirror our modern understanding of a religion. In Wright’s own words, he notes that religion “consisted of God-related activities that, along with politics and community life, held a culture together and bound the members of that culture to its divinities and to one another.” (p. 3) In other words, religion is not a wholly unique institution like a 6th-estate in a civilization, rather it is an underpinning superstructure upon which all other estates of a society (and perhaps not unreasonably, life) are based upon. To that end, Paul’s revelation when travelling on the Damascus Road is not one that does away with the old foundation and seeks to enact a revolution, rather it is a fulfillment and an elevation of what was already standing. Paul’s revelation fulfills the intended function of the original superstructure; a foundation that was deemed insufficient (or perhaps more accurately, unmaintainable) due to man’s proclivity for sin. If there is a singular point to take away from the opening sections of Paul, it is the message that the Apostle never switched religions on the Damascus Road, rather he experienced a revelation and came to a fuller and greater understanding of God and, by extension, man’s relationship to Him. Naturally, a devoted Jew would protest this explanation and the notion that there is an additional revelation that God has made known, otherwise what difference is there between the Christian and the Muslim or any other heretical offshoot of Christianity for that matter. Do not worry though, because Wright is not one to simply miss a chance to expound upon the nuances of Judaism, the contemporary response by Jews to this supposed revelation, and the continued importance that the faith has on Christian theology. Of particular note to me was a tangent that Wright included that concerned popular Christian eschatology, noting that:

“[Wright] assumed without question, until at least [his] thirties, that the whole point of Christianity was for people to ‘go to heaven when they died.’ Hymns, prayers, and sermons (including the first few hundred of my own sermons) all pointed this way…. the ‘heaven and hell’ framework we took for granted was a construct of the High Middle Ages, to which the sixteenth-century Reformers were providing important new twists, but which was at best a distortion of the first-century perspective. For Paul and all the other early Christians, what mattered was not ‘saved souls’ being rescued from the world and taken to a distance ‘heaven,’ but the coming together of heaven and earth themselves in a great act of cosmic renewal in which human bodies were likewise being renewed to take their place within the new world. (When Paul says, ‘We are citizens of heaven,’ he goes on at once to say that Jesus will come from heaven and not take us back there, but to transform the present world and us with it.)” (p. 6-7)

Wright continues in such a fashion for much of the early book, exploring the intricacies of Jewish thought, the relationship that Christianity has with such concepts, and the impact that these ideas had on people such as Paul in the early Church who were experiencing a seismic shift that affected every aspect of their lives.

With Wright’s introduction addressed, the body of Paul now stands ready to be engaged. However, this is where I begin to become torn as a reader. The early chapters of Paul were easily the most interesting in the book as they addressed many of the influencing factors that Paul and the early Church had to contend with during these years. Of particularly interesting note was the pervasiveness of certain historical figures in the (and forgive me if I am using this word incorrectly) contemporary Jewish zeitgeist. Of course, there are those like Elijah who was among, if not the most, important prophet Israel ever had between the Exodus and the year 200BCE. However, while Elijah was a model of religious zeal to Jews, and especially to the Pharisees (who would be rightly regarded as the more authentic religious Jewish sect when compared to their contemporaries, the Sadducees), I was surprised to read of the importance that Phinehas had on the Jewish culture. I should stress again that if the Jews kept figures like Elijah and Phinehas in their minds as models to replicate when envisioning their relationship to God, this impassioned fervour was doubly so for the Pharisees, of which Paul was originally a part of. For those perhaps scratching their head at the familiar albeit obscure name (or are now thinking of a particular Disney cartoon), Phinehas was the grandson of Aaron, brother of Moses, and practiced as one of Israel’s early priests. For those unfamiliar, there was a particular episode recorded in Numbers where Israel was living in Shittim, and the men of Israel ‘socialized’ with the daughters of Moab and began practicing Baal worship. This so infuriated the Lord that his anger was “kindled against Israel”, prompting the Lord to send a plague upon the people (Numbers 25:1-9). The Lord made known to Moses that if he took the chiefs of the people and hung them in the sun, that the Lord’s anger would be satiated; an action that Moses quickly undertook we are led to believe. However, one Israelite man had the audacity to take his Moabite lover into the tent of meeting to ‘know’ her. It is recorded that the event spurred the congregation to tears. Phinehas enters the story at this point, leaving the congregation and grabbing a spear before entering the tent of meeting and pierced both man and woman, ending the plague (25:7-9). Afterwards, the Lord specifically notes that Phinehas had turned away his anger and spared Israel from being consumed by the Lord’s jealous anger (25:10-11). Thus, Phinehas’ descendants were given a covenant of perpetual priesthood. Not finished though, the Lord also blessed Phinehas with a personal covenant of peace (25:12-13). For those familiar with the weight of a covenant, you know the seriousness of such a proclamation. It is the ultimate promise; the same kind made between God and Abraham as well as between Jesus and us. No doubt Paul was familiar with the importance of zeal and the desire the Lord has for it, a virtue that was no doubt ground into him fiercely throughout his training as a pharisee. This emphasis on religious zeal provides much needed context to Paul’s almost fanatical dedication to purging the seemingly heretical movement of Jewish dissidents that threatened the very foundation of their society. Wright paints Paul’s influencing factors vividly and it is impossible not to see these forces at work throughout Paul’s life not only as a Pharisee but also as an Apostle of Christ where he, perhaps more so than any other apostle, engenders a pure zeal for the Lord and his Kingdom.

However, this is where I must offer a small, but important point. If you are like me and are moderately familiar with Paul’s journey and the cities he ventured into, Wright’s moments of fascinating explanation are simply less frequent. While not unexpected given one’s familiarity with the subject, I have to admit that there were times that the reading came of as less engaging. This is largely due to the middle and later portions of the book having to shift away from defining our gospel figures’ cultural and religious influences and instead relying on conjecture (albeit well reasoned speculation) to explain the likely reasoning for Paul’s specific movements and intentions. I would not be so simple as to say the middle portion of the book was boring, by no means (there is far too much information to simply disregard these later potions as boring - that would be a disservice to the extensive research that Wright did). However, the farther and farther you get into the book you find that more and more of the events recounted are almost step-by-step recordings of what Paul did during his missionary journeys. With the shift in focus acknowledged, it should also be noted that while I found myself occasionally struggling to keep engaged, there are still significant portions in the middle and later portions of the book that proved riveting. Chapter 8 proved especially interesting as Wright analyzes the reality of Paul’s meeting with the leaders of Athens within the Areopagus, noting that this was less a friendly exchange of ideas and actually a trial with Paul on the defence. Consequently, Paul’s speech before the Athenians is almost completely recontextualized in many a person’s minds as our apostle’s impassioned speech is not just an explanation of a fringe religion’s creeds but an instance where we can see a true zealot fighting for both his life and the lives of those accusing him. It is in moments like these where Wright’s detailed and thoughtful commentary proves, most valuable as he provides important contextual information that we modern readers so often miss. However, there are also numerous instances where I could not help but find the explanations that Wright was offering bordered on the unnecessary. It is a shame, and perhaps on a second reading I may change my position on this statement and disown this portion of the review. However, at this point in time, I feel obligated to note that for those among you who are more versed in Pauline history, you will come across a number of ‘dry’ sections in Paul as the commentary Wright provides proves notably familiar.

With my one real negative noted, I want to expand on it a little more but in a different light. This ‘dryness’ is not out of some increasing passivity on Wright’s part, rather it is the result of us simply having less and less information as we get farther into Paul’s story. While books like Acts provide a great deal of information on the Church’s history and Paul’s journeys (with the author, Luke, even travelling with Paul for a limited amount of time), less information is available to contextualize many of Paul’s letters. Of particular note are the extended periods of time in which Paul is imprisoned and waiting to appeal before Caesar (p. 176). While this sparsity of information does give Wright the chance to speculate and infer likely situations that were occurring in the cities Paul had history with, the apostle’s headspace during certain key events, the challenges he and his party were facing, or the relations between leading Church figures, these tangents often did not satisfy my greedy desire for more knowledge. I should stress that this is not the case throughout the course of the book, definitely not. Chapter 6 specifically provides a very interesting analysis of the increasing tension between the Jewish-traditionalist and the Gentile-sympathizing parties within the Church. Wright takes great care to specifically highlight the strained relationships that Paul had with certain Church leaders such as Peter and James during the Jerusalem Conference, an event that likely defined much of these important figures’ future relations. While Paul never mentions the Jerusalem conference himself, it is nonetheless recorded by Luke in Acts 15, wherein he highlights the careful and strained relationship Paul will have with the church fathers for the remainder of his missional career as he balances the absolute necessity to keep the body of believers unified while also never compromising his zealous advocacy for a special revelation. Paul is arguing zealously for a realized plan, a fulfilled law, a redeemed Judaism, for Christianity. Wright beautifully illustrates Paul’s message and character in a way that not only seems real and human but also reminds us of the whole point of the apostle’s message, that being God’s gracious will in the form of Jesus Christ. While Paul may indeed have dry spells, there are these impassioned moments in Wright’s work that cry out to be returned to. However, while I will return to certain books in a heartbeat, Paul, unfortunately, has so many long and ‘dry’ sections that I can not find myself counting down the days to return to this book anytime soon.

If you are looking to learn more about the life and work of Paul the Apostle, I would of course recommend N.T. Wright’s Paul: A Biography. Wright carefully avoids needless and baseless psychoanalysis and instead prefers to highlight the undisputed influences that Paul would have encountered, specifically those of a religious nature. Furthermore, with a few exceptions, namely the later chapters wherein Wright speculates about Paul’s final years and a possible period of freedom after his final letter, he does not indulge himself with speculation (and the instances where he does often feel warranted). Instead, Wright reserves himself to investigations that are substantiated upon evident and accepted facts of cultures, histories, and religious features that would have impacted how Paul worked. However, if you are already familiar with Pauline history then you may find this read somewhat lacking. While this is by no means a bad thing, those of you who are looking for something meatier may be disappointed. To that end, Paul will likely serve the 1st and 2nd year Bible College student better than the seasoned professor as it provides a great analysis of Paul’s journey, though it does not spend a great deal of time expounding upon the minute intricacies of his message. In short, if you are simply looking to beef up your understanding and knowledge of Paul, this book will probably be for you. However, if you are a seasoned learner and are looking for advanced concepts or for Wright’s trademark eschatology, you are not likely to find what you are looking for here. With that said though, I quite enjoyed my time with Paul and am reminded that Wright is a dear blessing to our Church; without whom we would be all the lesser.

.png)

تعليقات